(This lays the ground work for the next post, which was getting too long to be effective.)

Overfitting

One of the goals of machine learning is generalizability. A model that only works on the exact data it was trained on is effectively useless. Let's say you're tasked with creating a bird-recognition system. If you train a model to recognize pictures of birds, and it gets 100% accuracy on the 130 pictures of 10 classes of birds you showed it, is it a good model?

It might be, but it depends on how the model performs on images it was not trained on. If performance measures on both the training set and the test set are good, then the model is performing well. But if performance on the test set is bad, then that model is not particularly useful. Through some mechanism, your model has 'memorized' the 1300 pictures you showed it. You already had those pictures, so you don't gain anything by using the model.

In an ideal world, your algorithm would be able to to discriminate between different types of birds, even if the pictures are very different from the examples it has seen before. To do that, it needs to identify features of those birds that are constant for each bird rather than features of a particular picture or photography session. There are a number of ways an algorithm might try to characterize a Blue-Faced Parrot Finch from this picture below, for eample. One good feature might be to recognize that the Blue-Faced Parrot Finch has an area on its face that is blue.

credit for this image: Wikipedia user Nrg800

credit for this image: Wikipedia user Nrg800

We might want to check another picture to see if this feature is consistently present.

credit for this image: www.cliftonfinchaviaries.org

So far so good. This picture of a Blue-Faced Parrot Finch also has a blue face; it seems like a good feature to use to characterize this bird. But what if the algorithm identified a different feature? In the first picture, the bird stood on a forked branch. If 'forked branch' was one of the features it used to identify this bird, it would not have generalized to all pictures of this bird. Or, in both of these pictures, the bird is facing to the right; the algorithm might decide that facing to the right is a defining characteristic of this finch. In machine learning, we call these cases overfitting: an algorithm learns non-generalizable characteristics only present in the training data.

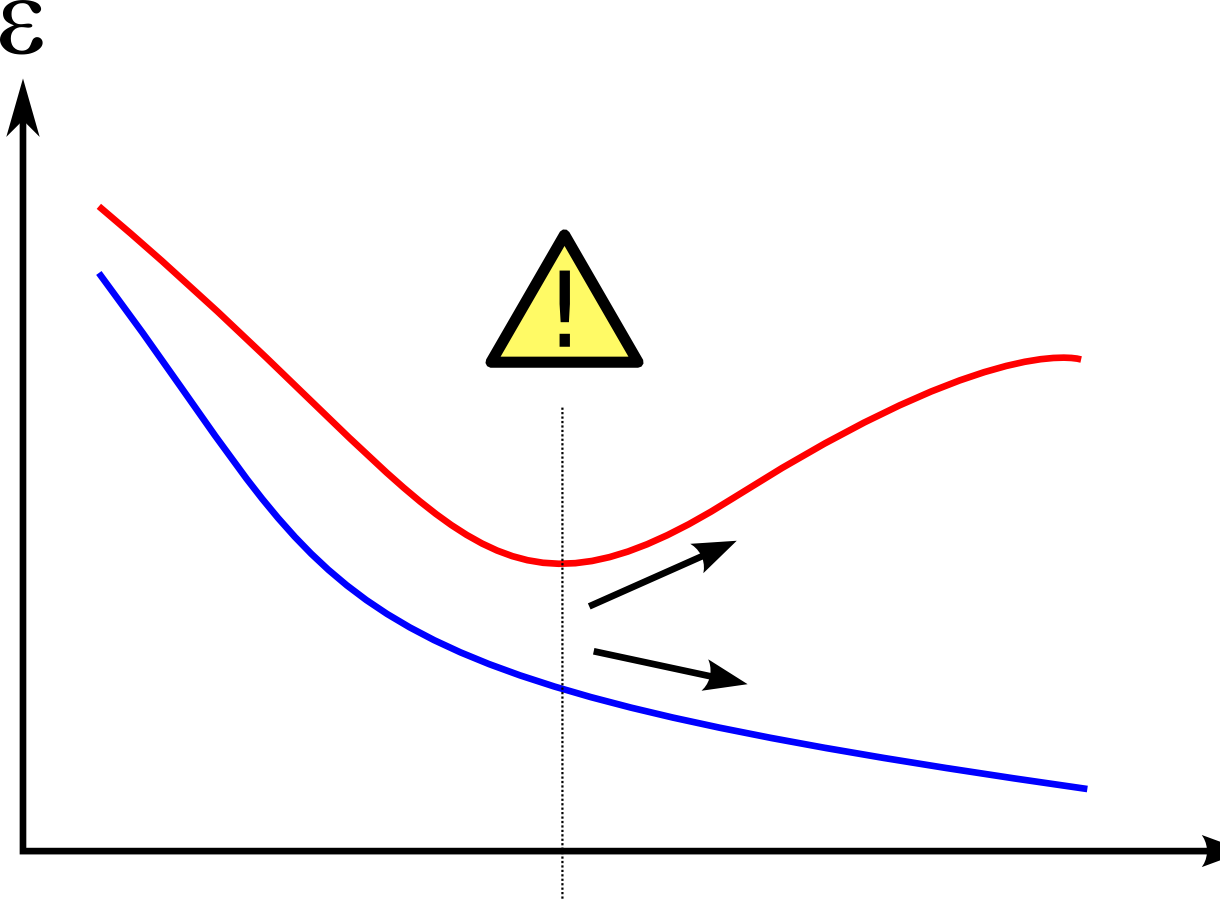

Overfitting is one of the hidden specters of the field. As the complexity of your model increases, the potential for overfitting increases as well. In this illustration below, the blue line represents the error rate on the training data, and the red line represents the error rate on the testing data.

h/t to Richard Corbridge for this clean overfitting graphic

h/t to Richard Corbridge for this clean overfitting graphic

As the representation capacity of your model increases, it is better able to capture variation in the training data, so the blue line monotonically decreases. The red line (testing data error rate) follows that trajectory initially: the model is learning things that are generalizable. But at some point, the model starts to learn features specific to the training data (like our forked branch above), and performance on the testing data begins to suffer: the test data isn't exactly like the training data, so the 'memorized' features hurt generalizability.

Regularization

But complex problems require complex algorithms that can make very subtle distinctions. Right now, almost all the fun tasks (computer vision, question answering, speech recognition, etc.) fall under that umbrella. If we must use a complex algorithm, how can we avoid overfitting?

The simplest way to avoid overfitting is to give the algorithms too much data to overfit on. By overwhelming the algorithm with data, you force it to decide what is important. An algorithm that only memorizes the most recent examples it has seen will be exposed by poor performance on the test set. An algorithm that is making wise choices about what is important for it to learn and what isn't, will improve when given tons of data. For most supervised learning problems, however, labeled data is often prohibitively expensive, so this solution isn't always feasible.

Another way to do that is to use a technique called regularization to keep overfitting at bay. Without going into details, this technique introduces a complexity penalty that "punishes" the machine learning algorithm for letting the parameters get too large (which usually means overfitting). That is to say, it incorporates a mechanism in the algorithm itself which restricts parameters of the algorithm to make it learn in a way we think is less likely to overfit. Regularization is wildly popular, especially in situations where the data is high-dimensional (lots of different variables).

Hyperparameter Optimization

When introducing a regularization method, you have to decide how much weight you want to give to that regularization method. You can pick larger or smaller values for your complexity penalty depending on how much you think overfitting is going to be a problem for your current use case. This exposes one of the open secrets of machine learning: the goal is to get the computer to learn how to make decisions automatically, but there are values (like the size of the complexity penalty) impacting performance that must be chosen.

Every machine learning algorithm has these values, called hyperparameters. These hyperparameters are values or functions that govern the way the algorithm behaves. Think of them like the dials and switches on a vintage amplifier.

There are different combinations of amp settings that are better suited to produce different types of sounds; similarly, different configurations of hyperparameters work better for different tasks. Hyperparameters include things like the number of layers in a convolutional neural network or the number of neighbors used in a nearest neighbor classifier, and they can have a massive impact on how the algorithm performs. Once, I used latent dirichlet allocation (a topic modeling algorithm) as part of a classification task, and I found that by changing the \(\alpha\) and \(\beta\) parameters, the prediction accuracy on my test set could vary from 0.04 to 0.41. That's an order of magnitude of difference based on fiddling with two dials.

Finding the best combination of hyperparameters is called hyperparameter optimization; it is almost impossible to beat state of the art methods without performing hyperparameter optimization. But there are some subtle dangers. Using one algorithm "out-of-the-box" and laboriously tuning hyperparameters for another example leads to an unfair comparison: in general, hyperparameter optimization squeezes out better performance. A better algorithm will in general outperform a worse algorithm, but sometimes, you can find the perfect combination of hyperparameters, which will allow the best-case version of the lesser algorithm to beat an average version of the better algorithm. Choosing the best hyperparameters is like playing with the dials of one amp until you find the perfect sound; It's not really fair to compare the sound of a perfectly-adjusted amplifier with one you use default settings on.

And most vexingly, hyperparameter optimization can lead to overfitting: if a researcher runs 400 experiments on the same train-test splits, then performance on the test data is being incorporated into the training data by choice of hyperparameters. This is true even if regularization is being used! With each time an algorithm is evaluated on the test data, that test data becomes less useful as an "unsullied" evaluator of performance. By the 400th or 4000th evaluation, the test data holds very little mystery and is no longer functioning as a test dataset; it has become a secondary training set.

There are some strategies that attempt to mitigate this problem: one is to use a train-validation-test split, where the hyperparameters are tuned based on performance on the validation set. This leads to potential concerns about overfitting to the validation set, but the test set is left more "intact" is cross-validation, where the data are split into \(n\) train-test sets. But this mostly just shares the overexposure problem with a larger test dataset (since everything is eventually tested rather than a small subset). But that sharing only postpones the inevitable. The problem still remains that exposure means evaluation is performed on a decreasingly 'unsullied' test set.

Wrap-up

In the attempt to move toward generalizable machine learning, we try to find algorithms that perform well on training data and testing data, using regularization to pursue that goal wherever possible. And, in general, if two algorithms achieve the same performance on a task, the one with less hyperparameter optimization is generally preferable.

Machine learning competitions that reward only the single highest-performing team provide a bit of a mixed bag, then. It's typically impossible to win those competitions without a great algorithm and some hyperparameter optimization. But it becomes difficult to separate the gains that come from better algorithms and the gains that come from more judicious hyperparameter choices. I'll get into this a bit more with my next post.