At the end of May, the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Competition, or LSVRC (currently the word's top annual computer vision contest) announced that a team had violated competition policies by over-submitting results. The follow-up post named a team from Baidu (the Chinese search giant) as the perpetrators of this offense and explained that Baidu had been banned from submitting results to the ILSVRC for a twelve-month period. MIT Technology review called it "Machine learning's first cheating scandal."

The search giant's response was swift. It's not really possible to remove a paper from arXiv.org, so the offending team did the next best thing: they replaced this functional draft on arXiv with this nonexistent one. And the primary researcher for the paper, Dr. Ren Wu, was fired from his position as "distinguished scientist at Baidu's Institute of Deep Learning."

To the non-practitioner, it might seem a bit extreme. Why would submitting answers to a contest too often be an offense worthy of termination for a promising academic with a good publication record? And why should an entire corporation be banned from an international computer vision competition over such a seemingly small incident?

In order to address that question, we're going to need to talk about some important concepts in machine learning. I talked about overfitting, regularization, and hyperparameter optimization in this previous post. Next, let's talk about benchmarking.

Benchmarking and Breakthroughs

Machine learning (ML) is a very performance focused discipline: academics in ML do a lot of theoretical work, but the algorithms themselves are generally compared based on their performance on tasks that have specified training and testing data. The core idea is that when different algorithms are tested on the same data, we can gain a more objective sense of their relative performance. There are some major advantages to this, namely the objectivity of well-designed experimentation and the fact that strong performance will help even obscure researchers' ideas rise to the top. We will talk about some of the potential problems with the focus on performance in a few paragraphs.

As an example of this benchmarking tendency, in 1998 Yann LeCun (now head of Facebook's FAIR and one of most influential researchers in computer vision) used the MNIST dataset to evaluate most of the computer vision algorithms people were studying at the time. Partially as a result of that effort, the MNIST dataset became one of the most popular datasets to evaluate machine learning algorithms on, and that particular article has had over 4200 citations.

Various other computer vision datasets have emerged through the years, such as Caltech 101, Caltech 256, and the PASCAL VOC (Visual Object Classes), but the release of ImageNet by Deng et al. was the great leap forward. There's so much to say about ImageNet (almost all of it breathlessly positive), but it's enough to say that ImageNet dwarfs previous computer vision datasets in both the number of classes and images per class.

Because of ImageNet's scale, the ILSVRC is a much more challenging competition than ones that came before it. With 1000 classes, the algorithms that succeed need to have high representation capacity, since they need to be able to discriminate between every class, which means there are \(n(n-1)/2=1000*(999)/2=499500\) decision boundaries between classes. In problems needing high representation capacity like this, more parameters are generally helpful; more parameters give an algorithm more room to hold what it has learned. Since multi-layer neural networks (shallow or deep) are universal function approximators that can accommodate unlimited numbers of parameters based on how you structure them, it makes sense that neural networks of some kind ("deep learning") would be an effective approach in computer vision.

One difficulty with deep learning is that deep neural networks with millions of neurons take a long time to train. This was helped by a significant breakthrough in 2012 by Alex Krizhevsky, a PhD student at the time at the University of Toronto. Krizhevsky famously used the parallel computational capabilities of graphics cards (GPU's) on a computer in his dorm room to drastically reduce training time for his convolutional neural network models. This meant he was able to train much larger models (with more layers and parameters and therefore higher representation capacity) than other researchers at the time, because he was able to obtain results in days rather than weeks.

That paper had a 10.85 p.p. lower absolute error rate than the next best result on ILSVRC 2012 (winning with an error rate of 15.3% compared to the second best's 26.2%). It was rightly hailed as a major breakthrough, and GPU training has become the standard method for training deep neural nets. I mention this story because it's a quintessential example of a major breakthrough in a field: a new technique or idea that is broadly applicable and improves the entire field.

Conclusions

The ImageNet ILSVRC has a rule in place that a machine learning system can only be submitted for evaluation on the test set twice a week. Since every submission needs to be evaluated on the same test set, this rule functions as a regularization parameter; limited access to submission makes for limited exposure for the competition's most guarded secret, the scoring test set.

This rule also restricts the amount of hyperparameter optimization, or in this case hyperparameter overfitting, that can be performed on the scoring test set. In machine learning, over time, the models tend toward better accuracy, because the best ideas tend to be absorbed into the best practices of the field (there are almost no papers focusing on 3 or 4-layer CNN's these days, for example). And in the days of widespread publication of pre-prints on the arXiv, those new ideas can spread through the community in a matter of days or weeks. Limiting submissions to twice per week means that hyperparameter optimization should only be able to have a limited effect relative to that overall trend toward forward progress. I think this is the most important reason for the restriction, and this is why the Baidu scandal mattered so much.

The Baidu team's oversubmissions tilted the balance of forward progress on the ILSVRC from algorithmic advances to hyperparameter optimization.

Here is the response from Dr. Ren Wu after the initial scandal broke:

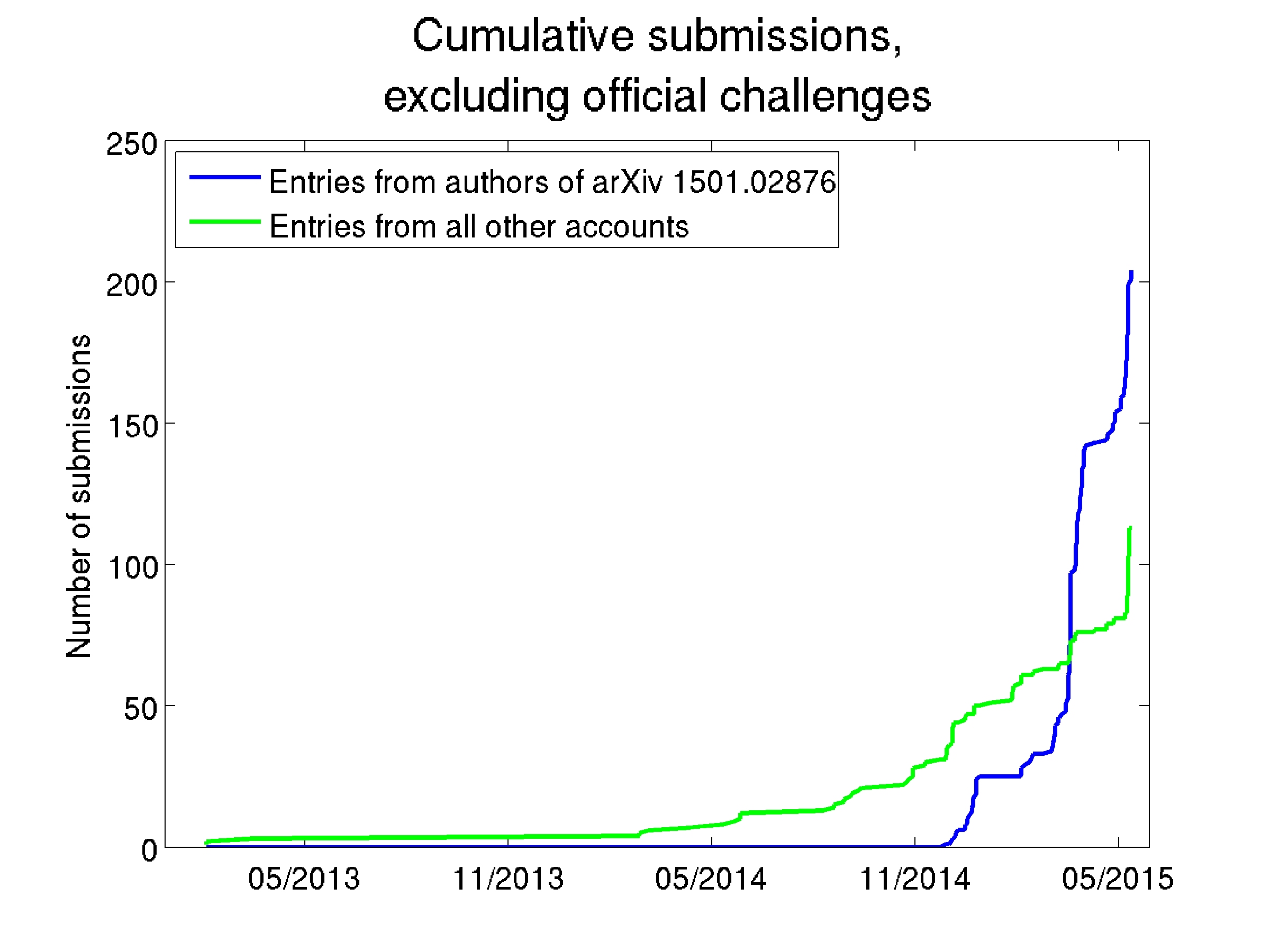

The "two submissions per person" argument is fairly weak: if true, it would incentivize gathering large groups of collaborators merely to get more frequent result submissions. That would be unfair to researchers at smaller universities or companies with fewer connections in the field. It would be patently unfair. A more problematic sticking point is that it appears no other team took this view of the submission policy. The graph below shows that the Baidu team submitted results more times than all other teams combined. (Members of the Baidu team had to create multiple logins in order to circumvent the "two submissions per week" rule)

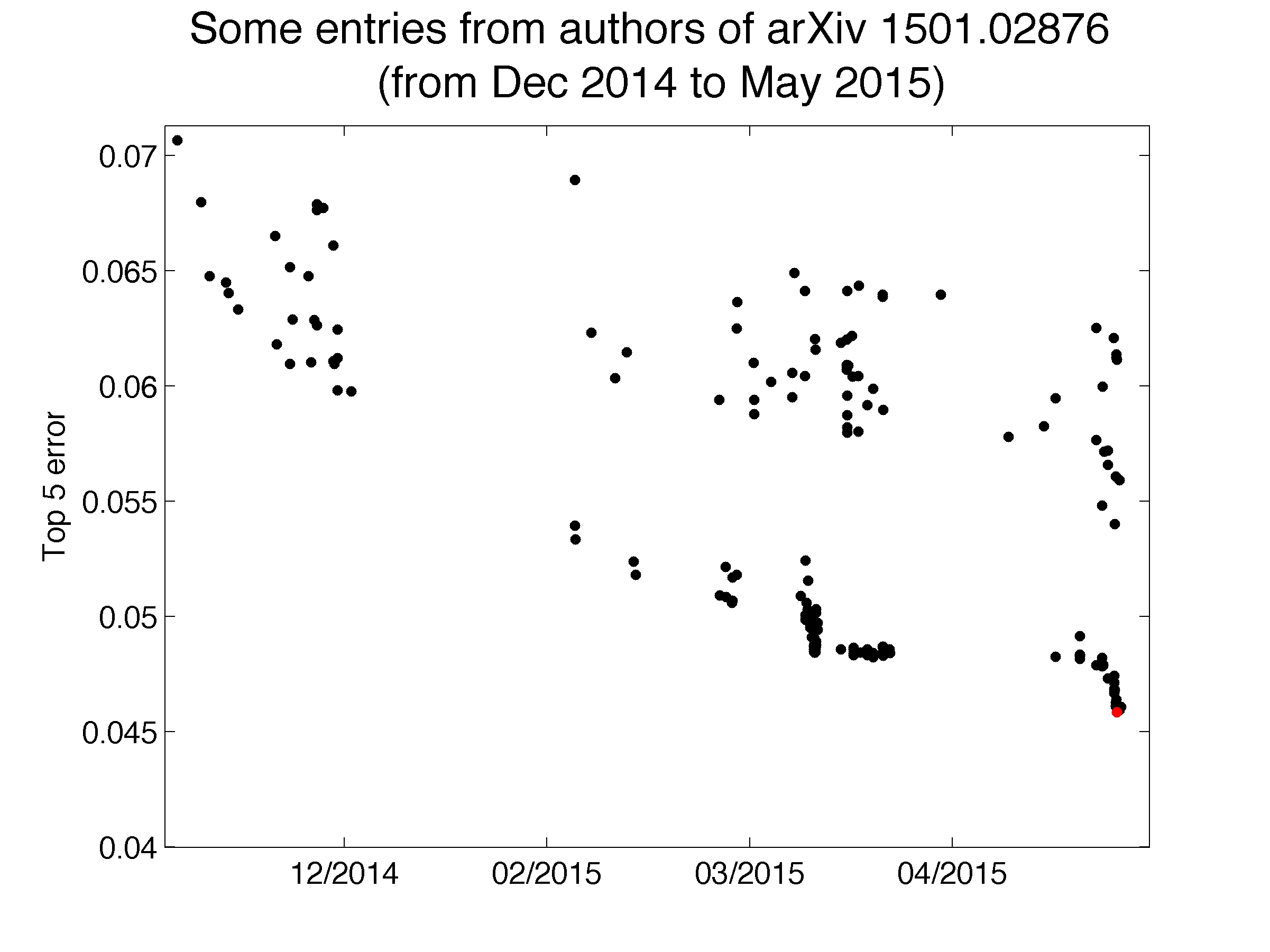

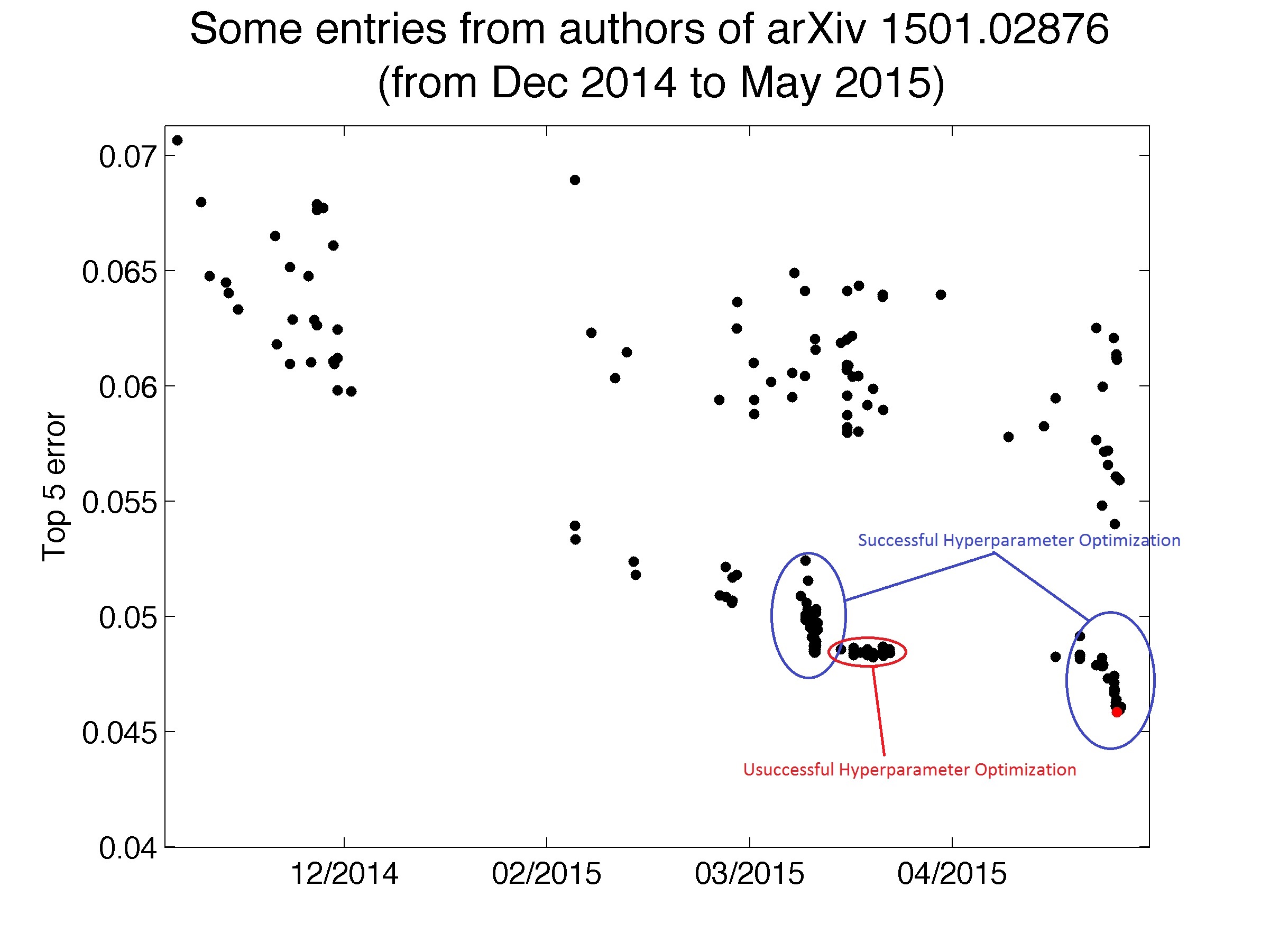

This might conceivably be acceptable if the team were trying out a variety of algorithms and hyperparameters and seeing what sticks. As an outsider, I don't have access to those records, so I can't make any conclusive observations. But the graph below shows their results over the period of time they were submitting, and it is quite informative.

There is an overall downward trend over that time, during which several other labs made major breakthroughs and received press coverage for achieving state-of-the-art results on the ILSVRC. Many of the results for the Baidu team are scattered in performance, as though the team was trying many things to see what worked and some of those ways were less effective. That's normal and probably healthy.

But if you look at the bottom right, there are three areas of more clustered submissions. I hypothesize that these are three periods of hyperparameter optimization. The cluster I've circled in red appears to have been relatively ineffective. But the two periods I've highlighted in blue were successful; the blue ellipse on the bottom right culminates in their 'winning' submission. In contrast to the 'great leap forward' established in the Krizhevsky et al. paper, the Baidu team's results show that hyperparameter optimization can still extract a little bit of performance out of algorithms in high-profile competitions.

This was intentional hyperparameter overfitting. Someone as experienced as Dr. Wu was would not have made such a mistake accidentally. It was bad machine learning practice; this looks like a deliberate attempt to utilize an unfair competitive advantage. When people think of "cheating" in a research context, they immediately think of fabricated results, but this violation also deserves that label.

Repercussions

Setting aside the scandal, the fact that the Baidu team achieved 'state-of-the-art' results on the ILSVRC by running hyperparameter optimization experiments likely means that the dataset is nearing the end of its run as the benchmark in computer vision. For the first time since its inception, the major ILSVRC classification challenge has a bounding-box component rather than pure classification, and this scandal probably contributed to that. The ImageNet classification task will still live on as part of the battery of proving grounds an algorithm is evaluated on, much like how MNIST still lives on today, but I look forward to seeing what the next gold-standard computer vision dataset will be. Perhaps something related to video processing?

And maybe we're all a bit complicit in the problems raised here. The field uses best-case test results to show how well an algorithm works. But using the maximum score achieved by a particular algorithm is an inherently outlier-dependent measure. Is the absolute best performance achieved in one particular experiment really the best measure of the capabilities of an algorithm? Doesn't this formulation inherently reward hyperparameter optimization? It would be very valuable to find ways to mitigate this outlier dependency.

And, finally, to make sure we aren't making lesser versions of the same mistake this Baidu team made, we should always use the train-validation-test framework (or even better, use crossvalidation for the train-validation splits). If you're comparing two algorithms, you should only evaluate each model on the test set once. Do all your hyperparameter optimization on the train-validation set, leaving the scoring test set as un-learned-from as possible. Hyperparameter optimization on the scoring test set causes results ranging from somewhat suspect to actually fraudulent.